Rachel Linnemeier’s subject matter includes powerful women in situations that both evoke strong feelings of nostalgia and inspire narratives. The overarching theme of Rachel’s work includes tension between the idea of modern adulthood and residual childhood. Each piece is composed of bright and vivid colors creating a youthful feeling while simultaneously expressing maturity through the pose and expression of the figure. Recent works have begun to explore the addition of landscapes to create complexity in narrative.

Ann Moeller Steverson | The Emotive Figure

Ann Moeller Steverson is an American artist known for her emotive and mood filled figurative works, primarily created with oil on copper. Her works are described as having a timeless quality which invites the viewer to create their own sensitive response and narrative through a compelling tension and sense of mystery. Through the quiet intensity of each piece she seeks to share her most authentic self, what she loves, and an invitation for connection. Born in Huntsville, Al, in 1980 she continues to reside there, working within a vibrant artist community. There she paints, teaches, and operates an atelier to promote the advancement of realism in modern painting.

Amy Ordoveza

Amy Ordoveza is a contemporary realist artist who creates detailed, imaginative still-life paintings. She carefully crafts and arranges the delicate cut-paper plants, animals, and architectural elements that she depicts in her oil paintings. The fragility of the paper objects suggests impermanence while Ordoveza’s close observation and meticulous handling of paint hint at their significance. Her compositions evoke a sense of beauty and mystery in ordinary surroundings.

Ordoveza received her MFA from the New York Academy of Art and her BFA from the Maryland Institute College of Art. Her historical influences include 17th century Dutch still life painters including Rachel Ruysch and Jan Davidsz de Heem as well as surrealists such as Kay Sage and René Magritte. Ordoveza’s work is included in the Lunar Codex and the Nova Scotia Art Bank and has been featured in publications and websites including American Art Collector, PoetsArtists, and Booooooom!

Pauline Aubey

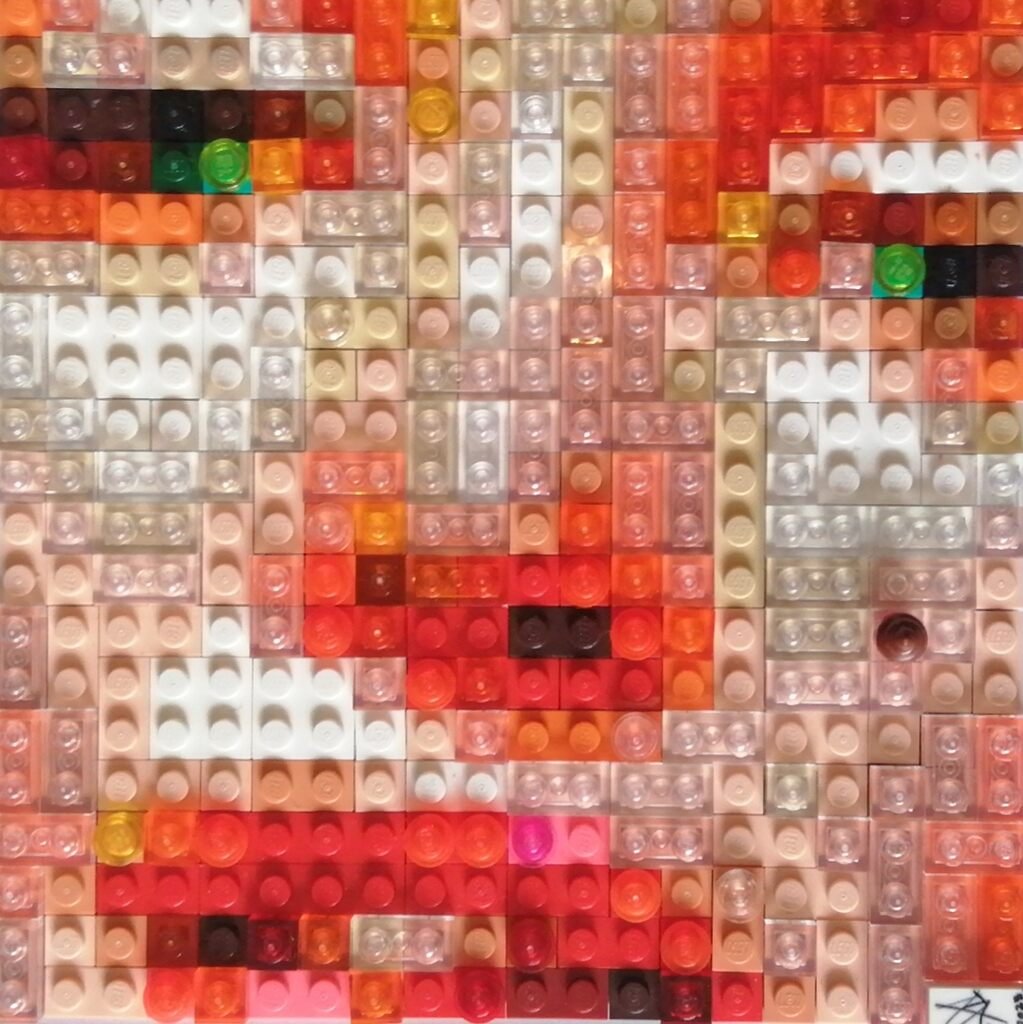

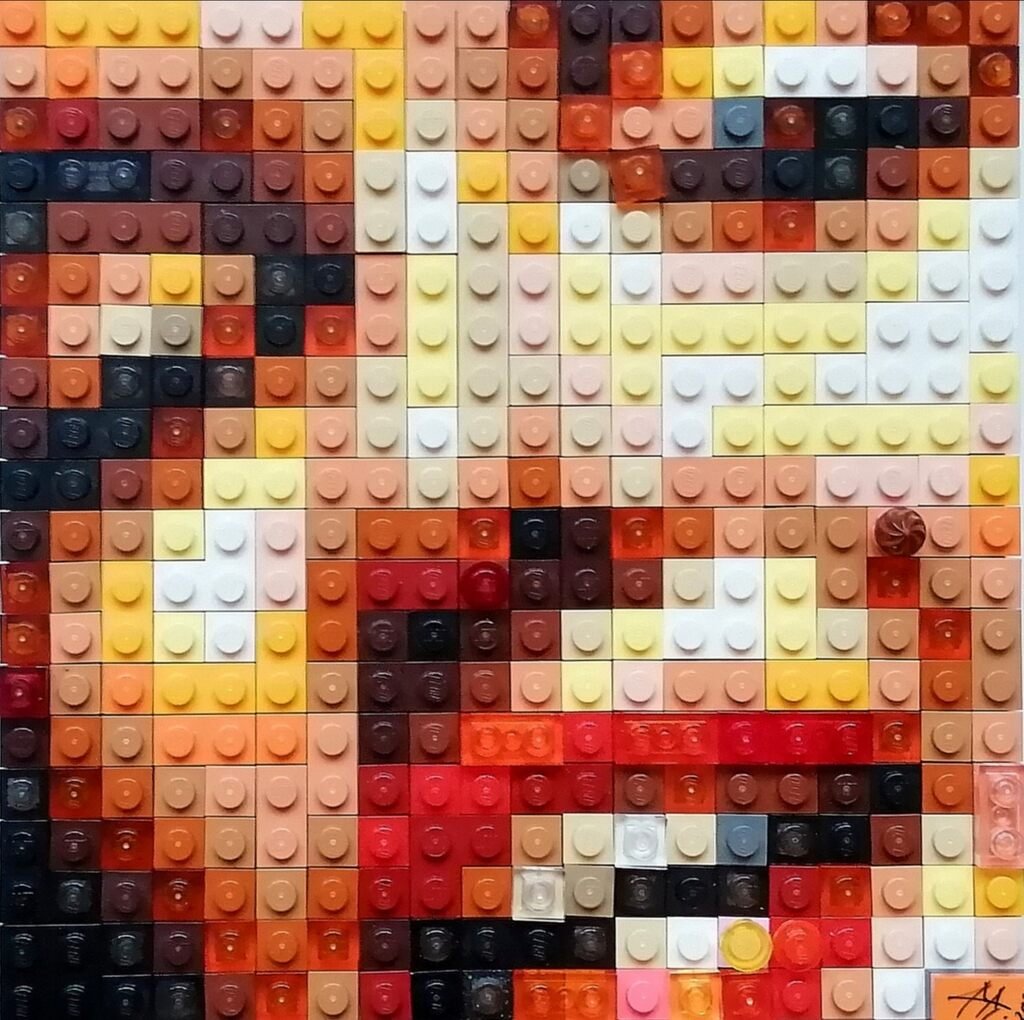

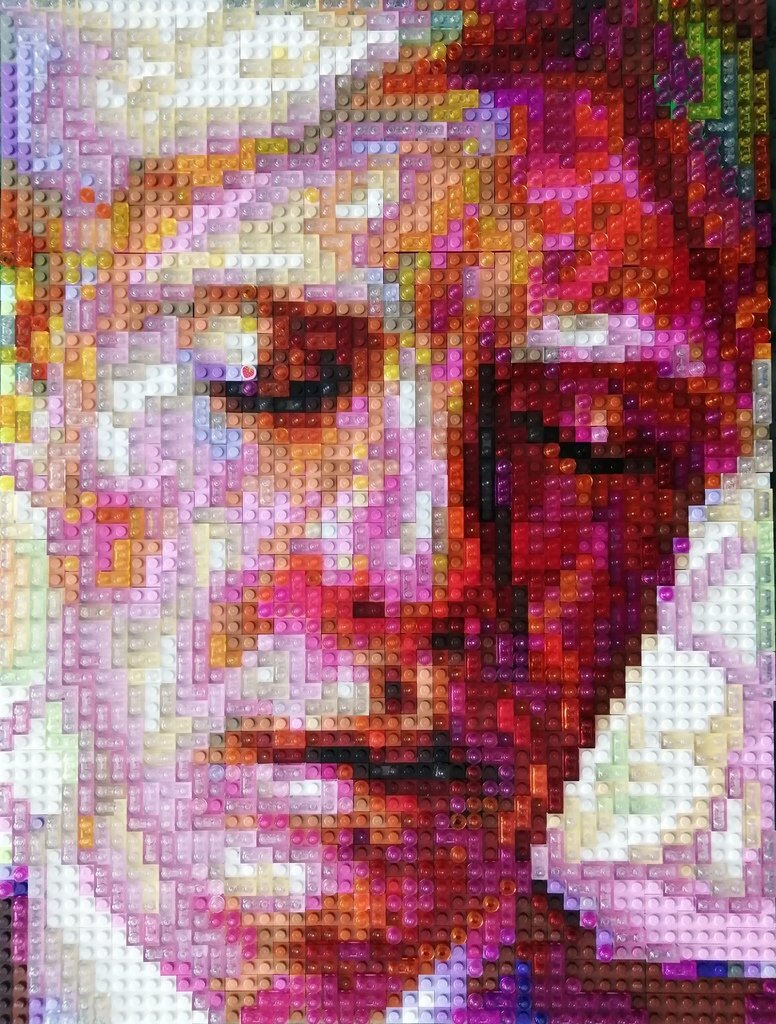

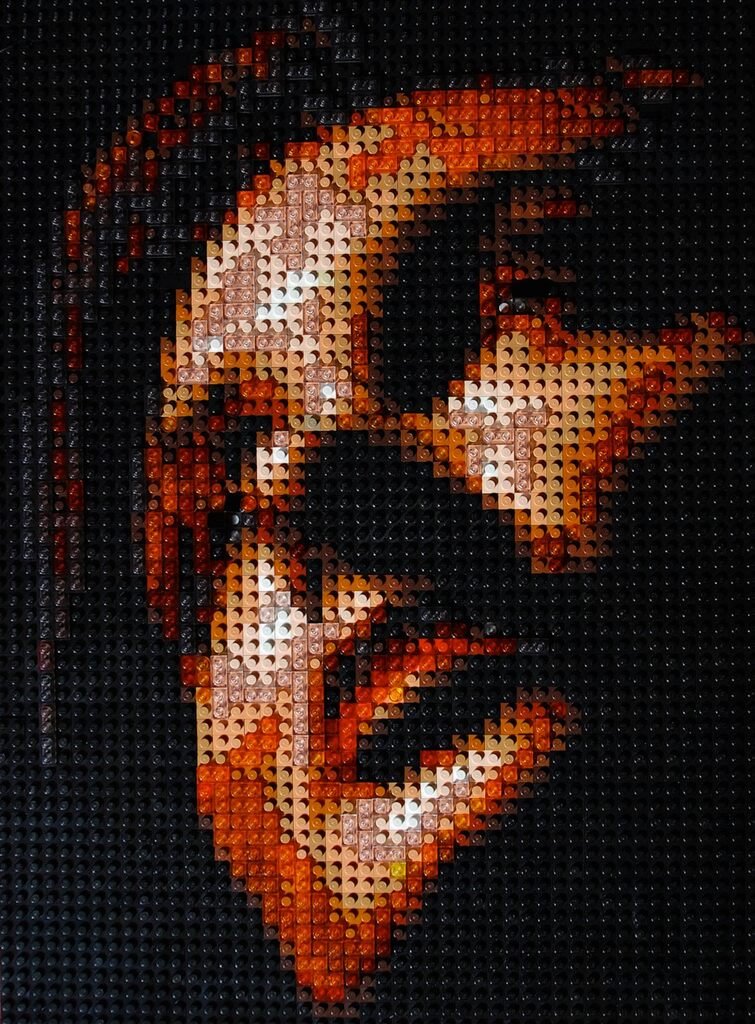

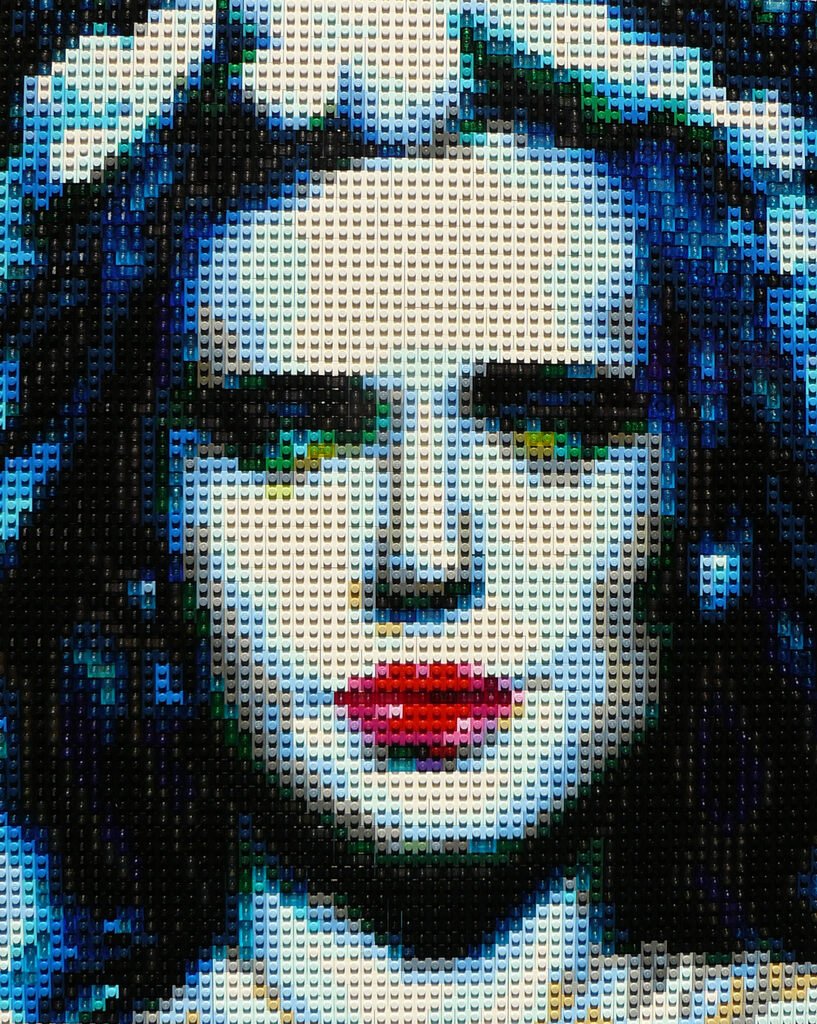

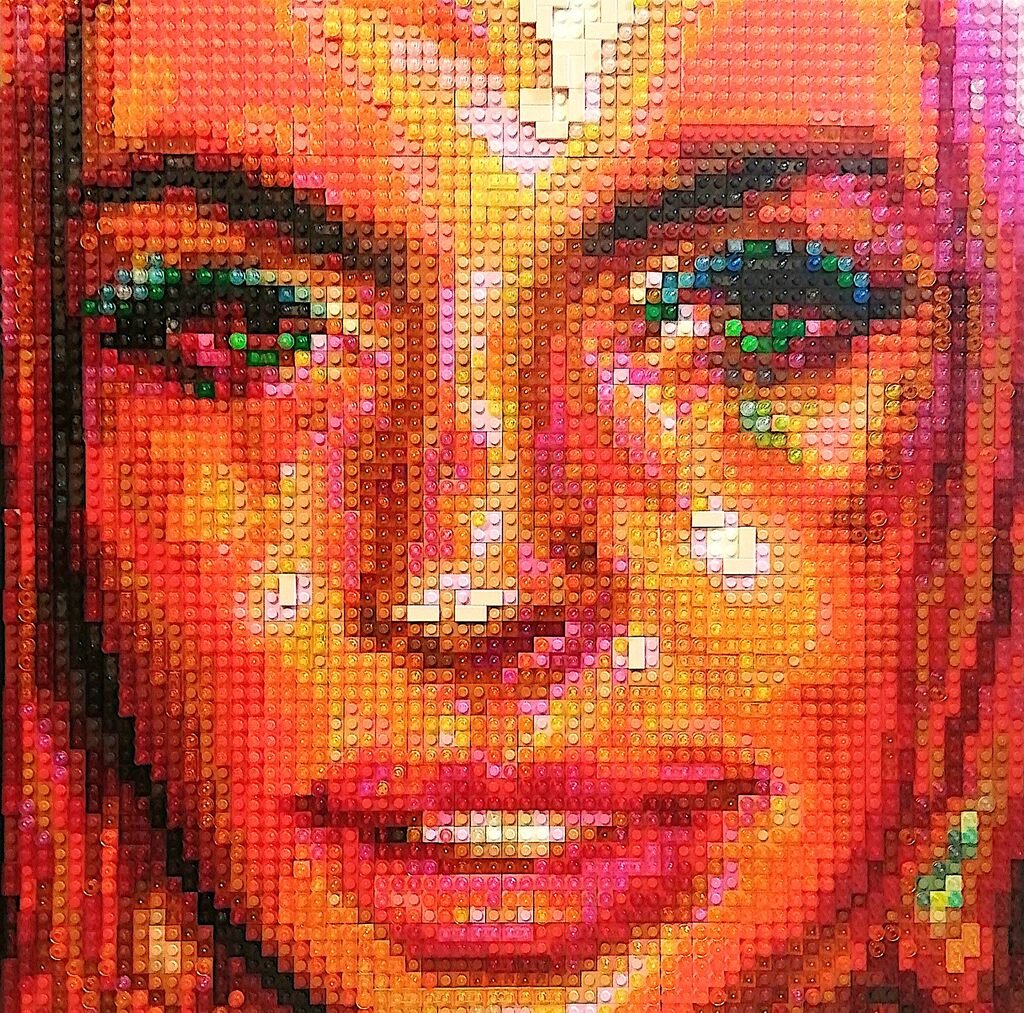

Paulina Aubey’s LEGO portraits ingeniously merge popular form with popular content in order to question our relationship to celebrity. Having begun her artistic career working with pastels, Aubey’s passion for pop culture inspired her to try her hand with a more popular medium: LEGO bricks. She has elevated this unusual medium to the status of fine art, creating expressive portrayals of contemporary icons and the idols of her 1980s childhood. Her portraits of religious figures, movie characters, and pop stars—including David Bowie and Marilyn Monroe—blur the distinction between figurative and abstract art. They appear highly detailed from a distance and become pixelated upon closer inspection; this viewing experience prompts audiences to reflect on how much we can ever truly understand our idols. In order to create her portraits, Aubey chooses a digital image of her subject and manipulates it to create the desired expression and color scheme before selecting appropriate blocks of LEGO to build the work.

Erica Calardo

Erica Calardo is a figurative painter living and working in Italy. Her works in oils, watercolors, and pencils are windows on the solitude of lost souls. She explores the realm of Beauty, Grotesque, and Magic, by creating eery oneiric feminine figures who tell tales of long forgotten dreams, of an imaginary timeless past.

Deeply rooted in the Italian Tradition, her technique is inspired by the Renaissance and Mannerism old masters (Leonardo, Bronzino, and Lavinia Fontana above all). She is mostly self-taught and has learned her skills from old dusty books. She has recently studied academic painting with Italian master Roberto Ferri.

Since 2010, she has showcased her work in galleries in Italy (Mondo Bizzarro, Studio21), and abroad (La Luz de Jesus - LA, Auguste Clown - Australia, Modern Eden, Swoon, Flower Pepper, WWA, and Spoke Art, Distinction - USA, Pinkzeppelin - Berlin among others). Erica's paintings have appeared in several magazines and books, like Miroir Magazine, Beautiful Bizarre, Il Manifesto, Inside Art, Italian Pop Surrealism, Illustrati.

Ariane Kamps | 10 QUESTIONS →

1- What is different from your art work than other artists working in contemporary realism?

My work is different in that I tend to use a lot of punchy colors, lots of neons, etc and the subject matter is often centered around modern problems, mostly concerning how technology is affecting society on a spiritual level. My goal is to create modern mythologies.

2- How important is the process versus the end result?

The process means a lot to me, I enjoy a lot of the little things. I enjoy sanding panels of all things, gilding the edges with gold, little things like that. I'm always excited to begin a piece. That initial excitement is what carries me through the long process that becomes the end result.

3- What is your ultimate goal when creating contemporary realism?

I want to have a conversation with the viewer about our modern life, the choices we make each day and the world we're ultimately building.

4 -What do you like best about your work?

I like to creating little worlds and making peculiar dreams become reality. It helps me think about the issues we're facing when I can see it represented.

5- What do you do you like least about your work?

I dislike having to explain the meaning or inspiration behind the work because I often don't have a "message" attached to each work, just loose ideas that I wonder about when I look at each painting.

6 -Why contemporary realism?

I'm a very literal person, I get stuck on details which is useful in realism and I've found a safe haven in contemporary realism. I feel like the artists that work in contemporary realism are pushing boundaries and asking important questions, it really feels like an art movement that is alive and growing.

7- Which are your greatest influences?

I love the work of Frank Frazetta not only for his fantastical worlds and narrative work but also because, not unlike myself, he started oil painting later in life. He was very gutsy, and made being true to himself and his vision paramount. I also love the work of Mucha, Klimpt, Monet, and Waterhouse. In terms of living artists I'm very moved by the work of Kari-lise Alexander, Ali Cavanaugh, and Kristin Kwan.

8- What is your background?

I didn't end up going the conventional education route but much of what I learned was from fellow painters, workshops and what I could find online.

9- Name three artists you'd like to be compared to in history books.

I would feel honoured to simply be mentioned in a history book, I can't imagine being compared to any of the incredible talent out there today.

10- Which is your favorite contemporary realism artwork today?

I love this egg tempura piece by Julio Reyes. It feels timeless yet still contemporary.

Lorena Lepori | 10 QUESTIONS →

LORENA LEPORI

Lorena Lepori's figurative oil paintings have a narrative based on the representation of feminine figures beyond gender, relating to everybody who can express the power of femininity. She uses cross-dressing to reach out and create iconic alter egos to expand and embrace a hidden part of her models’ personality through look transformation. She relies on myths, fairytales and clichés challenging the traditional representation of the matters, re-introducing them in a contemporary setting, mixing old and new symbols to relate more with universal concepts.

What is different from your art work than other artists working in contemporary realism?

I believe intentions are what makes every work unique. Mine are unpredictable, sometimes. I am mostly inspired by personal memories, abstract feelings and references from movies and music I grew up with. This combination of elements characterizes what I produce.

How important is process versus the end result?

In my case the two are deeply connected. Once the right idea hits me, the creative process evolves quickly; subjects, backgrounds, outfits and props are already in the picture before I touch the brush. They are so clear to me, that ,rarely, I found something different from what I have planned on my canvas.

What is your ultimate goal when creating contemporary realism?

Make the viewers curios about the references and amuse them with the twist I like to add in the composition.

What do you like best about your work?

In the process I like the attention I give to the concept. In the end, I like to see the materializing of my abstract idea.

What do you do you like least about your work?

I would love to be more spontaneous, less obsessed with technical details.

Why contemporary realism?

I consider myself a pragmatic soul, but nothing trigs me more than realistic figures, amazingly executed, immersed in the abstraction of an idea.

Which are your greatest influences?

My very first love was Tamara De Lempicka, flamboyant colors and beautiful women in glamorous and swoony poses. I think I got my imprinting from her, and that would explain the focus of my attention into feminine figures.

Caravaggio, and his incredible dramatic work, definitively represents a level I have always aimed to. Last but not least, Gustave Klimt who stimulated my curiosity with his ethereal pale women, wrapped in symbols and flat fabric.

What is your background?

I used to be a cartoonist and illustrator in my twenties. Life drove me away from that world for several years. Only in my forties I went back to my original passion, and I started to train myself as a painter, with the help of artist friends and a lot of self-teaching. It is now 9 years that I am totally committed to oil painting. And I love it!

Name three artists you'd like to be compared to in history books.

I would love to see my name mentioned next to the three artists named above, that would be of course very ambitious and not very humble.

Which is your favorite contemporary realism artwork today?

A huge masterpiece by Sergio Martinez - The portrait of Desire

Gemma Di Grazia | 10 QUESTIONS

1. What is different from your art work than other artists in contemporary realism?

Unlike still life, landscape painting or botanicals, my flowers are my live models. They have personality, express emotion and have a narrative. The story of my flowers is a dialog between color and the shapes they create; and the conversations can be harmonious, complementary, or energetic.

2. How important is process versus the end product?

The process of painting provides such joy. I love the fluidity of the oil paint, and the satisfying control of my brush. The discovery of the palette as it reveals itself is like watching an engrossing movie. Time doesn’t exist when I’m painting, I’m simply in a zone, a headspace of hundreds of intentional decisions flowing from my mind. The end product is, as some say, “when I stop painting.” To conclude a painting is to finish a good book: resolved and better for the experience.

3. What is your goal when creating contemporary realism?

My goal is to sell my work, so I may afford to continue painting! I heard Audry Flack say recently that art is healing; that can be for the artist and the viewer. Flowers are life-affirming, and beautiful. Beauty itself is healing, whether creating or appreciating it.

4. What do you like best about your work?

My new series of floral paintings fuse representational florals with elements of design. It is exciting and hopeful to make work with the goal of expressing beauty.

5. What do you like least about your work?

I have many more ideas than I can paint. Editing is crucial. My painting process takes time, so I never have enough.

6. Why contemporary realism?

I enjoy painting what I see, then putting it through my filter and express the beauty.

7. Which are your greatest influences?

My parents, who were artists.

8. What is your background?

A family of artists contributed to my early interest in art. My grandmother, mother and father all attended Cooper Union for art. My mother was a painter and my father, Thomas Di Grazia was a published illustrator and painter. I attended LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and then earned a B.F.A. from Hunter College. I also studied at S.V.A., Parsons, and the Art Students League of New York.

9. Name 3 artists you’d like to be compared to in the history books:

Instead of artists from history, I’d rather be along side the many artist friends whose work I admire.

10. Which is your favorite contemporary realism artwork today?

It is difficult to choose just one particular favorite contemporary realism painting, but some of my favorite contemporary artists are: Xenia Hausner, Hope Gangloff, Audry Flack, and Janet Fish.

Di Grazia’s representational paintings are a celebration of color, light and form. Her compositions exhibit formal aesthetic elements, whether using soft pastels or oil paints, she uses a luminous and vibrant color palette that transform the formal foundation into something exciting and dynamic. Her work seeks to evoke the life-affirming beauty inherent in the natural world, and reveal what is extraordinary in the familiar. Ultimately, it’s not the subject matter that interests Gemma, it’s the tone, the gesture, color, light, scale and composition, that continue to absorb and inspire her.

Michael Van Zeyl | 10 QUESTIONS

1- What is different from your art work than other artists working in contemporary realism?

I think my work looks different because I work in three picture planes, a foreground, midground and background and they are clearly separated by dimensional feeling. I like to play with texture and use color harmonies to push the near too far feeling. I think the individual elements of my paintings are realistic but the overall composition is imaginative.

2- How important is process versus the end result?

I spent so much time developing a process with oil paint using material surfaces that were mostly handmade. I hoped to create textures that were not seen before. Being a painting teacher, I surrounded myself with more people who were focused on technique and HOW to paint. When you have a show and you discuss your work with more non-painters you learn they are talking about and focus on the final image and WHAT you painted.

3- What is your ultimate goal when creating contemporary realism?

To paint my truth but ultimately connect with a wide enough audience which make my paintings immortal.

4 -What do you like best about your work?

It is a reflection of my thoughts.

5- What do you do you like least about your work?

How long it takes me to call it complete.

6 -Why contemporary realism?

Because when I walk out of every museum and art fair I visit that is the genre that stays with me and can’t stop thinking about.

7- Which are your greatest influences?

I’m going to go with the living ones because I had the opportunity to study with all of them starting with David Leffel then Steven Assael and weekend with Bo Bartlett.

8- What is your background?

I went to art school with a focus on illustration and design. I began painting after art school at the Palette & Chisel Academy where I was able to paint with dozens of great artists and talk art talk art 24/7.

9- Name three artists you'd like to be compared to in history books.

I like Vermeer for his thoughtful picture making, I like Thomas Dewing for his etherial quality and made up color harmonies and I like Degas because when you think of dancers you automatically think of him.

10- Which is your favorite contemporary realism artwork today?

Daniel Sprick’s Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.

MICHAEL VAN ZEYL

Michael Van Zeyl is a full-time artist living and working in Chicago. His formal training began at the American Academy of Art, continuing on at Chicago’s Historic Palette & Chisel Academy. His art has been featured in several publications such as: American Art Collector, PoetsArtists, and American Artist magazine. Michael’s work is already appreciated in many public and private collections, such as the United States District Court, University of Chicago and was the 2014 recipient of the Dorothy Driehaus Mellin Fellowship for Midwestern Artists.

Emma Kalff | 2022 Year in Review

Emma Kalff is an American visual artist based in Colorado. She is a representational oil painter whose work recreates the surreal atmosphere of dreams. A road trip across the USA inspired a series of works that resulted in her first solo exhibition in Telluride, CO. Additional recognition followed, and in 2022 the artist’s work was featured in Southwest Art magazine 21 Under 31: Young Artists to Collect Now. Kalff studied at the New Orleans Academy of Fine Arts.

Was 2022 a good year for you? What were some of the highlights in your art career?

This year I was published in Southwest Art's "21 Under 31: Young Artists to Collect Now", Aesthetica magazine, as well as in American Art Collector. I am so thrilled about being published in these magazines - it's certainly an elevation of my career. It gave me the push I needed to go into painting full-time.

How has social media affected your daily practice?

Social media is a lot to keep up with! Often I find that I just want to paint when I'm in the studio, but I end up having to film and photograph a lot of the process for social media content. I'm happy to be able to share my process at the same time though. It's a bit of a double-edged sword.

What are you looking forward to in 2023?

I'm very excited to continue working on my current series of paintings, Holding Your Horses. I have spent the last few months building up a large portfolio of work, and I look forward to building relationships with gallery owners in the Southwest and beyond.

E X E R T I O N curated by Daniel Maidman

I have been thinking lately about what an artist owes his or her audience. The audience shows up; they volunteer their time and attention; they make themselves available to see, to be moved, to change. The artist is asking for a tiny fragment of the life of the audience.

This is a moral responsibility. How can it be discharged?

I suppose there are many ways. I have always thought I owed my audience the best and most profound ideas and images I was able to summon. But as I made these offerings, I found that I was boring my audience.

The root of the problem was apparent – the angel Damiel expresses it well in Wim Wenders’s 1987 film Wings of Desire:

“It's great to live by the spirit, to testify day by day for eternity, only what's spiritual in people's minds. But sometimes I'm fed up with my spiritual existence. Instead of forever hovering above I'd like to feel a weight grow in me to end the infinity and to tie me to earth. I'd like, at each step, each gust of wind, to be able to say Now. Now and now and no longer forever and for eternity. ... At last to guess, instead of always knowing. To be able to say ah and oh and hey instead of yea and amen.”

Some artists grasp from the beginning that the substrate of their art is not oil paint and canvas, or bronze or marble, or what have you, but entertainment. For my part, it took me a lifetime. It took me thirty years to learn that no artist is too good to entertain his audience. Without entertainment, without moving the audience, no channel opens to communicate all those other essential ideas and images.

I learned this principle, and later I embraced it, and later still I practiced the techniques of entertainment. For all my technical skills, I am still shaky at making a thing that meets its first obligation to its audience – to hold their attention.

Human beings pay attention to stories. Not just in writing and theater, but in pictures as well. Conflict is the root of stories, and conflict plays out as struggle. To struggle, one must exert - the protagonist and the antagonist exist in a state of exertion. Jacob wrestles all night with the stranger in the desert.

To hold the attention of the audience one must oneself exert, and capture the sense of exertion, whether physical, emotional, or spiritual.

For this collection, I wanted to see how my fellow artists responded to the concept of exertion, to the call to raise the energy of their work. Each has brought their own interpretation to the question.

Some understood it as I intuitively understood it – a state of muscular effort on the part of the central character, as in David Morris’s drawing of a model in an unstable pose, Jeffery Mathison’s sprinting sunlit figure, Sheryl Boivin’s drawing of a woman straining mid-workout, and Elena Degenhardt’s ecstatic vision of bubbles swirling around a vigorous swimmer.

Others grasped exertion in the sense of conflict, and present figures in conflict with their environment – such as Emma Kalff’s woman versus menacing landscape, Evan Goldman’s peculiar man in the mountains, and Lisa Rickard’s Atlas-like allegory.

Several artists took inspiration from performance; Ingrid Capozzoli Flinn and John Hyland reference dance, while Daggi Wallace coordinates color and pose to evoke either singing or a shriek. Patricia Schappler portrays a boxer practicing – one of the few artists to submit work rooted in sports.

There were a few sui generis pieces: Amy Gibson invokes anxiety with concealment and thorns and Lorena Lepori creates a similarly distressing image through a woman tattooing her own neck. Geoffrey Lawrence creates a disquieting modern interpretation of Saint Christopher carrying the Christ child.

Finally, there was Sarah Gallagher’s highly rendered portrait of a woman with an ambivalent expression and a shadow cutting across her throat. Beneath the seeming serenity and repose of this image there lies a struggle, the nature of which we cannot determine, but only feel. The image not only opens itself to interpretation, but demands it; we cannot tell what is going on, but we know that something is. In seeking answers, we, the audience, begin to exert as well. Gallagher demonstrates the use of entertainment as substrate, as portal to all those other transcendent things we crave for our art to communicate.

Painting the Figure Now: Exploring the Human Condition

The human figure is easily the most relatable of fine art subjects, but it is also easily the most complex. That complexity is not just from learning how to accurately paint the human anatomy, but also in deciding how to convey the emotion, life and experience of the figure to fit the composition. Add to that an artist’s individual style—ranging from conveying all the details to fixating on the atmosphere—and you have a multitude of elements that bring the image to life.

In the annual Painting the Figure Now exhibition, presented by PoetsArtists at the Wausau Museum of Contemporary Art, the human experience is on full display. This year’s show, happening July 7 through October 2, is guest curated by art collector Dr. Samuel Peralta who says the addition of Now to the title is the true anchor and theme of the show.

“Figure painting has a long and historical tradition—but for these series of exhibits, the art has to have a perspective that’s contemporary, compelling and current,” says Peralta. “The PTFN series present Polaroids in brushstrokes, as it were, of the human condition Now.”

In selecting the just under three dozen works, Peralta turned to works with a symbolic undercurrent or narrative that allow the viewer to explore the painting. “Including this doesn’t have to be an overt or conscious process—it can emerge subconsciously during composition and be available to be inferred from the finished piece,” he explains. “For me, the question to ask was: Was the artist successful in conveying that intention to me through their portrayal of the human figure?”

What resulted is a show that demonstrates, for Peralta, that work with “the vocabulary of modern accoutrements remains true to its historical, even classical, traditions.” Many of the artists with paintings in the show have atelier training where life drawing and painting classes were at the core of their curricula. Or they take inspiration from great masters—past and present—but with an eye for the contemporary world in which they are living. And, perhaps, something that should be noted is the paintings of the past were once present too.

There are some artists participating, such as Megan Elizabeth Read, who are outside of the box and didn’t grow up surrounded by the arts or have formal training. Instead, their own work has been an evolution through time and experience.

Read says, “I was always drawn to figurative work as a child; it was really the only thing that interested me and since I have no formal training or background in the arts it made sense when I began creating my own work I would simply gravitate toward the type of imagery I was most moved by.” From a technical standpoint, Read’s artwork has become more simplistic over time and she leans into a minimalistic approach to the materials that helps manage her process.

“More importantly, this need for reduced ‘noise’ and chaos in my real life is directly reflected in my paintings in that they tend to contain large canvases and are generally fairly simple compositionally,” she explains. “There is a lot of room to breathe there and creating these spaces helps me feel less fragmented. Less pull in too many directions. It’s like I am painting away the clutter and chaos.”

Since she started painting, Read has evolved the narrative in her artwork but has found some themes to weave their way through her oeuvre such as “the search for identity and the concept of constructed identities, the need for and fear of vulnerability, and this idea of multiple selves.”

Her work in the show, Nobody Showed Me Which Way to Go, plays into the themes because the work is about “the loneliness and confusion of being dropped into this world without a map or support system and the struggle to find one’s way under these conditions. About dragging yourself along amidst the beauty and terror we are faced with every day,” Read shares. The imagery comes from her personal experience of this feeling this. Growing up she was surrounded by cows, and sees herself reflected in them, so they are a nod to constructed identity and figuring out how to move through life.

Annie Louise Goldman is a young artist at the start of her career, and what direction she will take is still unfolding, but for now a passion for the figure has propelled her to new discoveries. Growing up Goldman did family portraits, and at age 13 she wanted to take a life drawing class. She enrolled in an art school in San Carlos, California, which she attended until she was 17 studying under artists such as Noah Buchanan.

“I learned about Baroque painting from Noah, and when I started was really fixated on composition, lighting and drama,” she says. “I also was doing Bard copies in a very 19th-century academic style. That’s been really influential as over the last couple of years I’ve started to explore a more contemporary side of art such as the work of Florine Stettheimer and Alice Neel.”

As a student currently at Laguna College of Art + Design, Goldman has started to develop narratives that are connected to her experiences. They are often very intimate narratives, and that’s reflected in how she approaches her work. Everything she does is derived from life drawing, but to get the right composition she will now take photos of her models, who are usually also friends. The narrative can come to life as she’s photographing, or there are times Goldman has a fully developed idea before the shoot starts.

In most of her work, Goldman wants to show the connection people have with one another. Her selected painting, Playtime, is an intimate moment of a couple undressing one another. Goldman says, “At the time we took the photos, the two women were a couple,” says Goldman, “so I was able to capture an intimate moment. The title reflects the innocent looking image, but it has sexual undertones…it isn’t portraiture or about specific people. It’s meant to reflect however the viewer is coming at the image.”

The idea that classical figurative imagery can hang next to any interpretation of the figure in exhibitions today is something that artist Chris Cart says allows artists to have more freedom in expression. This can come back to the figure itself, because instead of having a tight, classical image, the artist can interpret the mood or emotion in the way that suits the composition.

Cart’s work In the Waters eloquently combines multiple figures in a surrealistic move among the waves. The painting, which he says is about love, community, mindfulness and life as a dance, was started over a decade ago as a tightly rendered naturalistic piece, that was sanded down and repainted several times. The “blue lady” came in early, and maybe at first was subconsciously what Cart needed to experiment with the artistic process. A while ago he began to play with using multiple styles in one canvas and created what he calls “mashups in paint.” In the Waters as a result is a harmonious intertwining in composition and style.

“To me, artist has always meant depicting life as I see it around me,” says Anna Cyan. “Painting the Figure Now is in some ways about building a bridge across time—drawing on the long history of showing the body through paint but using this language to examine the here and now. Painting is a dialogue, not just with the past, but also with the future.”

Vulnerability is a theme that often appears in Cyan’s artwork, but this spring it came into focus on an even greater level and as a reflection of the present. “I am from Ukraine, and as I worked on the painting [that’s in the show], war coverage brought home how fragile the human body is, and the immensity of violence and destruction that can threaten it,” Cyan explains. “Initially, the painting was going to have a much lighter sky, but as the war unfolded, smoke started creeping in, and the overall tonal range got darker. So now the painting is called Smoke. When I look at it, the sound of air raid sirens plays in my mind, and it’s as though the character hears them too, in her world. They are distant, but there.”

Erica Calardo sees the exhibition as a chance to focus on the greater reawakening in the art world to relearn how to depict the figure—using Old Master techniques and skill, but painting for our times. Calardo shares the initial sentiment of the figure being “the most challenging subject within representational arts. Both technically and theoretically.” For her, reflecting humans in a realistic rather than idealized manner is important.

Reverie is Calardo’s first painting of a male figure and she wanted to depict him more than just as muscular and grand, full of physical strength and power.” Instead, the work is about intimacy and dreams, showing the man as someone who can have true and rich feelings. “My painting shows a person deep in dream and meditation, caught in his reverie,” she explains. “It is a very intimate and simple composition.”

Connecting to the “now” through modern fashion and topics is a highlight of Amy Gibson’s artwork. While always about the human condition, her most recent paintings focus on children and how they look at the world still with wonder and excitement. And it’s a reminder to the adult viewers to remember how they once saw the world as well.

Gibson’s painting They Said the Answer Was 42 is about technology and information overload for children today as they are exposed to news, social media and more at a fast rate. “That made me think back to the late 1980s when social media didn’t exist and I read a book called The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy,” says Gibson. “The character was able to ask the all-knowing computer created by advanced aliens a question. He wanted to know the ultimate question of life, the universe and everything. The computer told him that the answer was 42. That left him even more confused. I feel like kids are feeling this way. They don’t know the questions to ask in order to filter through all of the chaos so they can actually find an answer. This is leaving them filled with anxiety and ambivalence.”

Each painting in the show condenses the theme by intimating a moment or expression of the human form. However, when viewed altogether, Painting the Figure Now “traverse[s] the range of emotional responses for each individual work” says Peralta. “We will see the gestural and expressionist range of the human face and body by seeing the collection as a whole.”

Along with the show at Wausau Museum of Contemporary Art, the works are available to purchase through 33 Contemporary’s Artsy page, and digitalized images will be included in a time capsule on the moon via Peralta’s Lunar Codex project.

“The Polaris time capsule will be launched via SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket in 2023/24 and deposited on the Lunar South Pole via the Astrobotic Griffin lunar lander, which will also be carrying NASA’s VIPER rover to the moon,” says Peralta. “With the three time capsules of the Lunar Codex archiving art, writing, music and film from over 20,000 creatives from over 100 countries around the globe, the [PTFN 2022] artists will be joining the most expansive contemporary cultural exposition ever launched from Earth.”

About the Author

Rochelle Belsito is an experienced art writer and editor, having worked for International Artist Publishing for over 11 years in several positions. She served as managing editor for all five of the company’s titles for over seven years, and her most recent role was executive editor of American Art Collector, American Fine Art Magazine and International Artist. Currently she is a freelance contributing editor at Art & Antiques magazine and writes and edits for various other industries.

Q&A with Hyperrealist Matthew Quick

“A conceptual surrealist, I combine technical virtuosity, an inquiring mind and a love of storytelling, to make quirky, often humorous, observations on the world around us. ”

Featured in BRW as one of Australia’s top 50 artists, Matthew Quick began painting as a teenager before being one of the youngest students to study art at the University of South Australia. Upon graduation Quick joined Emery Studio in Melbourne, designing for major corporations such as Rio Tinto, Fosters and BHP.

After a prosperous career in design and advertising and having written a number of fiction books, Quick returned to painting in his mid 30’s. In the past few years he’s won, or been a finalist for, 70 national juried art awards. He’s had 14 solo and more than 80 group shows. His work is included in the permanent collection of Australia’s most significant museum.

CURRENT SERIES

Matthew Quick’s exquisitely created paintings turn a mirror on our contemporary online existence in his latest body of work The Mirror Electric. The artist’s visual commentary drives to the heart of the imagery that populates our social media feeds. Ricocheting from the amusing to the vacuous and absurd, his reading of the new visual shorthand of the online world is as sharp as ever. The mirrored surfaces and the ensuing interplay of one’s own reflection and the rendered surface of the painter’s hand is an immersive experience.

Q&A

What is your ultimate goal for your artwork?

All of the paintings are intended to engage the viewer with a narrative that operates on a number of levels.

At its most basic, it is intended to be intriguing, engaging and, hopefully, beautiful. However, it the viewer chooses to look a little deeper, layers of additional stories are revealed. Upon the combination of title and image, deeper meanings emerge, triggering the opening chapters to an endless array of stories the viewer is invited to create.

What concept or narrative is behind your work

The goal is pursue conceptual ideas that reveal societal issues and contemporary thinking.

This is achieved by subverting symbols images of power with irony and humour. Statues and monuments were my starting point, as they frequently map the rise and fall of Empires with overt symbolism, providing the foundation for a revisionist take on the notions of beauty, pride, and nationalism.

By replacing their crowns and thrones with ordinary objects, the aura of emperors and gods are demoting to powerless nobodies. Through ridicule, I play with their initial grandiose goals, querying their motivations and questioning the orthodoxy of accepted history. In doing so, I reference themes such individual freedom, social control, surveillance, and the deceit of rulers who intentionally fail to act as they speak.

THE PEREGRINE COLLECTION

News Release : On a Time Capsule to the Moon with 1200 Artists and One A.I.

TORONTO, ONTARIO (March 11, 2021) – The Peregrine Collection – an assembly of thousands of creative works by over 1200 creative artists and one A.I. – is headed for the Moon.

Coordinated by Dr. Samuel Peralta, the Artists on the Moon (AOTM) project is joining NASA’s scientific payloads on Astrobotic’s Peregrine Mission One, the first commercial launch in history, on a United Launch Alliance (ULA) rocket to Lacus Mortis on the lunar surface. Dr. Peralta, a physicist and entrepreneur, is also an author, whose fiction has hit the Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestseller lists, and whose poetry has won awards worldwide.

“I was fourteen on my first launch, an Antares model rocket kit by powered by an Estes solid-propellant engine the size of my thumb,” said Dr. Peralta. “Now we’re on Astrobotic’s lunar lander on a ULA Vulcan Centaur rocket headed for the Moon. Wow.”

The centerpieces of Dr. Peralta’s payload are the 21 volumes of his own Future Chronicles anthologies, all Amazon bestsellers, and 15 PoetsArtists art magazines and exhibition catalogs, one of which he helmed as guest curator for publisher and art curator Didi Menendez. Each individual volume provided scores of curated contemporary art and short stories for the time capsule.

Together with other art books, anthologies, novels, music, and screenplays - including for the short film Real Artists, which won an Emmy® Award in 2019 - he and his colleagues have digitized literally thousands of art and fiction for the trip to the Moon.

Dr. Peralta noted that between AOTM and its sister project, the Writers on the Moon group coordinated by fellow author Dr. Susan Kaye Quinn, several thousand creative artists and writers are now represented for the lunar journey.

“Our hope is that future travelers who find this capsule will discover some of the richness of our world today,” Dr. Peralta said. “It speaks to the idea that, despite wars and pandemics and climate upheaval, humankind found time to dream, time to create art.”

The Peregrine Collection represents creative artists from all over the globe, including from Canada, the US, the U.K., Ireland, Belgium, Australia, Sri Lanka, Singapore, and the Philippines. It includes a collaborative human-AI work of poetry between Dr. Peralta and OSUN, an OpenAI-based machine programmed by Sri Lankan author and researcher Yudhanjaya Wijeratne.

The Peregrine Collection is among the most diverse collections of contemporary cultural work assembled for launch into space, and is believed to be the first-ever project to place the work of women artists on the Moon.

The digitized artwork and literature files are contained in two microSD cards, encapsulated in DHL MoonBox capsules. Delivery is by Astrobotic’s Peregrine Lunar Lander, through NASA's Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program.

Launch is scheduled in July 2021 from Cape Canaveral, Florida, and the lander will touch down in the Lacus Mortis region of the Moon, marking Earth’s return, and the first mission carrying commercial payloads, to the lunar surface.

About The Peregrine Collection:

The Peregrine Collection brings together the work of 1200 creative artists, and one A.I., on a time capsule to the Moon, via Astrobotic’s Peregrine Lunar Lander. Digitizing thousands of artworks, stories, and more, it leverages the Astrobotic/DHL MoonBox initiative to bring one of the most expansive cultural collections to space. A project of Incandence under its Artists on the Moon initiative, The Peregrine Collection is headed by payload coordinator and curator Dr. Samuel Peralta.

Website: peregrinecollection.com

About Samuel Peralta:

Physicist, entrepreneur, and storyteller, Samuel Peralta's fiction has hit the Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestseller lists, and his poetry has won awards worldwide, including from the BBC, the UK Poetry Society, and the League of Canadian Poets.

Acclaimed for his Future Chronicles anthologies, he is an art curator, an award-winning composer, and a producer of independent films, including The Fencer, nominated for a Golden Globe®, and Real Artists, winner of an Emmy® Award.

With a Ph.D. in physics and an expansive career, Samuel serves on the board of directors of several firms, and mentors start-ups at the University of Toronto’s ICUBE accelerator.

About the Publications:

The majority of the artworks being digitized and being sent to the moon are from the publications made possible from PoetsArtists creator Didi Menendez. The publishing house is GOSS183. The designers for these are April Carter Grant and/or Didi Menendez. The publications are available to download from www.iartistas.com or buy in print from Amazon, Blurb, and Magcloud.

Marc Trujillo: ‘Nowhere And Everywhere’

Painter Marc Trujillo, who paints airports, big box stores and the occasional bag of potato chips with Vermeer-like candor, is currently having two shows: one at the Bakersfield Museum of Art and another at the Winfield Gallery in Carmel. Working with banal material, Trujillo generates scenes that attempt walk a fine line between the ordinary and extraordinary. Carefully modulated and cannily observant, Trujillo’s canvases show us that the places we barely notice can be recast as scenes of unexpected grandeur.

John Seed Interviews Marc Trujillo

MARC TRUJILLO |1644 Cloverfield Boulevard‘, 23” x 31,” oil on polyester over panel

Marc, where did you grow up and how did your childhood shape you?

I’m from Albuquerque, New Mexico, it’s big sky country like Montana and the land keeps you aware that you’re a small figure in a vast landscape which makes sense to me as a worldview and manifests itself in the paintings in the way I tend to scale the figures, they’re important but are held in check by scale. As a child, I only wanted to draw and read books, so my parents put me in gymnastics which gave me a good sense of discipline and I also realized that painting was something I could do my whole life, as opposed to gymnastics which has a short shelf-life.

MARC TRUJILLO |6333 Commerce Road, 24.75 x 23.5, oil on polyester over panel

How did your studies at Yale, and your interactions with Andrew Forge help you mature as an artist?

Graduate school is where you go to have the philosophical core you operate from thoroughly cross-examined. Andrew Forge would parse out distinctions that were fine enough to nudge and refine the way you thought. He defined ‘Artiness’ as ‘when the aesthetic effect is a consequence of things known beforehand’, for example.

William Bailey was also important to me as a model of making sure what you were doing was really painting. There are different forms and why something should be a painting as opposed to a song or novel or photograph should be a part of your intention or area of investigation from the outset. While a painting may show a place, for Bailey ‘the painting is the place.’ A painting has an autonomous reality as a painting and Bailey’s teaching and paintings both bear this out.

MARC TRUJILLO |8810 Tampa Avenue, 26 x 33 inches, oil on aluminum 2015

You are known for painting subject matter that others might consider banal: when did you realize that ordinariness held a special attraction for you?

The chill of the void is alluring to me. These places that are nowhere and everywhere, big stretches of concrete and linoleum give me a chill that makes me want to paint them. Also, when a painting goes too low or too high in terms of subject matter it plays to easily into people’s fantasy lives, and showing something that the viewer fantasizes about is narrative poison to me.

Joyce defined pornography that way: when you show the viewer something that they want to possess. I think he got this from Kant who said that the greatest experience you can have in front of a work of art is the “God-like moment’, which is disinterested pleasure; the pleasure you get from the paintings is not because you want what they are showing you. The low temperature of my subject matter also helps keep the painting the thing, to go back to the point about ‘the painting is the place.’ If I paint something like Mount Everest or the Grand Canyon then the painting reminds you of this greater experience outside of itself, like a postcard. On the other hand if I’m painting a gas station or Costco, then the painting has a chance at being more of an experience than you had when you were there.

MARC TRUJILLO |John F Kennedy International Airport, 16 x 27 inches, oil on panel, 2015

Tell me how the works of Jan Vermeer have informed and influenced you.

First of all by being part of what made me want to paint in the first place; my reaction to them came before my reflection about why they’re so good. Then you go back and look at them as a painter instead of as a fan so that you can bring something back to you own work, Vermeer’s paintings are superbly composed and balanced, the light in them is as important a character as anything in the painting, and his sense of scale is very refined.

JOHANNES VERMEER | View of Delft, 38 x 45.6 inches, oil on canvas, 1660-61

View of Delft is a pretty perfect painting, when you’re standing in front of it, it’s large enough to have some physical scale to it, but intimate enough that you don’t notice the size of the painting before you see what Vermeer is showing you. View of Delft is about 38 inches high, so if I’m not sure how large to make a painting, then I’ll make it 38 inches high by whatever width I need for the composition. I’ve made quite a few 38 inch high paintings.

MARC TRUJILLO |6350 Laurel Canyon, 40 x 60 inches

Tell me about one of the paintings you have on view in Bakersfield. How did it come about, and what kind of impact do you want it to have on viewers?

I think the show as a whole helps show how the work is made and am grateful to the curator, Rachel Magnus, since it was important to us to show how synthetic the paintings are- I make them like one frame movies, building the set (The vanishing point is the first thing on the painting), lighting it, and casting it. Making as thinking is vital to me. since I need to do a lot of drawing to more fully imaginatively own my subject as well as to distill my visual motive for making a painting of it, the muted narratives in the painting are all kept that way so that the viewer is the most important figure in the painting.

My area of investigation has come out of the work, rather than starting with a narrative and painting it, there are also cases filled with sketchbooks which I work in steadily, plein air paintings and studies from life: all of this is part of the food chain with the studio paintings at the top. It helps since some viewers might misunderstand the paintings as being ‘photorealist’. Since scale is important, I hope people experience the work in person, to continue from the last question; the actual painting is the result and the test of everything that goes into it.

MARC TRUJILLO | 517 East 117th Street, 25 x 44 inches.

So, to answer your question by singling out a painting, 517 East 117th Street is 25 x 44 inches. My motive for painting this was the red carpet of meat that you get when you stand in this spot in Costco. This painting is shown along with the composition drawing for it and there’s an iPad on the wall as well with various stages of the painting in progress. This preparatory work also determines the scale and we’ve grown too accustomed to the fluid scale that things we see digitally has: are you looking at it on your phone or is it being projected on a wall? People mostly look at things on screens, so both scale and tactility suffer, as well as the sense of light that I take a lot of pains to calibrate out of what photography gives you, which the fixed iris of the camera rolls back.

Is it fair to say that you are — in your heart — a very traditional painter who sees yourself as part of a long unbroken lineage?

Bringing the long, slow, patient way of looking and making to bear on the places we’ve made for ourselves that are hardly meant to be looked at at all is an important counterpoint of tradition and our contemporary world. In ‘Tradition and the Individual Talent’, T.S. Eliot couches a healthy relationship to tradition and that it needs to include the historical sense: ‘This historical sense, which is a sense of the timeless as well as of the temporal and of the timeless and of the temporal together, is what makes a writer traditional.’

And it is at the same time what makes a writer most acutely conscious of his place in time, of his own contemporaneity.’ Eliot also points up that tradition has to be earned and is not automatically inherited and opposes it to what people sometimes think of as tradition ‘ following the ways of the immediate generation before us in a blind or timid adherence to its successes.’ So, yes would have been the short answer but the word tradition is mostly used in the sense of following and the criticality of it gets lost sometimes.

MARC TRUJILLO | 7950 Santa Monica Boulevard, 16 x 35 inches, oil on linen over panel

What are you interested in outside of painting?

The sister arts, literature, sculpture, music (I play guitar some and am the first name on the music credits for ‘El Mariachi’, Robert Rodriguez’ first movie). Linda and I like to go hiking together and have a Rottweiler Ursa, who is a rescue dog.

MARC TRUJILLO | Oil sketches of Ursa

Exhibitions:

The Bakersfield Museum of Art

January 26, 2017 - May 7, 2017

Marc Trujillo ‘Urban Ubiquity’

Winfield Gallery, Carmel, CA

February 1 - 28, 2017

Interview with Elizabeth A. Sackler

Elizabeth Sackler and Gloria Steinem with 2014 Sackler Center First Award Honoree Anita F. Hill. Photo credit: Elena Olivo

On April 25, 2017 I sat down with one of my Sheros, Elizabeth Sackler, an activist for social justice, equity and equality. Elizabeth is deeply involved in the social justice communities and adds fuel to far reaching feminist action. She is the founder and president of the American Indian Ritual Object Repatriation Foundation and the visionary and impetus behind the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum. As Judy Chicago says, ‘Elizabeth Sackler is a force to be reckoned with’. After a warm welcome we jumped right in.

VS: The ‘New Feminist’ issue of PoetsArtists wants to tap into what’s happening on the New Feminist frontier. The work being done at The Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art seems to be the epicenter of rising feminist action as well as feminist art. I imagine you, Elizabeth, with your finger on the pulse and hands in the mix, bringing people together, instigating awareness and change.

ES: A lot of my work at the museum now is feminist social action oriented. In terms of feminist art in the gallery world, I don’t work in those universes.

VS: That’s exactly why we wanted to talk to you. For me, the Brooklyn Museum is not only focusing differently than the gallery scene but you’re redefining what it means to be a museum. The way you’re approaching activism and community involvement is redefining ‘museum’. I see the Brooklyn Museum as a ‘change agent’.

ES: Yes it is and it is because of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center of Feminist Art. I was very fortunate to have a great partner in Arnold Lehman who was the Brooklyn Museums director at the time that I brought him my idea for the Sackler Center. That vision was not for a gallery, but for a center. There’s a difference between having a gallery where you have only art and having a center where you have everything. Where you have lectures, where you have different kinds of exhibitions and where you can really break ground. That was really my interest.

My concept was to use Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party as the fulcrum to the center in addition to offering it permanent housing. This was for Judy a critical moment. She said, ‘Hurrah, it’s done’ and I said, ‘No, it’s just beginning.’ Because for me, The Dinner Party is a launching pad for every conversation. The one thousand and thirty eight women of The Dinner Party represents one thousand and thirty eight disciplines. There isn’t any area of life that it doesn’t touch. It is educating us about the past women who were feminists in their own right, even though the word didn’t exist, who were really breaking ground and doing things. Many of them of course were punished for it. Many of them were killed for it. We have this horrible history of oppression and women faced it with the grit and the will and the desire. Women who couldn’t be stopped. You can’t help it. You just go ahead. Didi Menendez, would know that. If your D.N.A. is made like that, then whatever your vision is that simply has to be and if that means change, that means change. The Dinner Party for me is a launching pad for all our programs and dialogues.

The Sackler Center layout breaks down with the Dinner Party Gallery at its nucleus, then the Feminist Gallery, the Herstory Gallery and the Forum. The Herstory Gallery is next to The Dinner Party and historically we’ve had small exhibitions there that have been extremely important.

Catherine J. Morris, The Sackler Center’s Senior Curator, produces more exhibitions each year than any other curator in the museum. We bring forward Herstory.

The Herstory’s very first exhibition used pieces from the museum’s Mesopotamia collection to reflect back some of the very early women in The Dinner Party, women from Greece goddesses. It was the first time in the museums history that there had been interdepartmental loan; where one department gave art for exhibition to another. That changed the functioning of the museum. It became in what academia is called interdisciplinary.

It was very interesting because when I signed the agreement with the Brooklyn Museum, in 2001, I didn’t expect to see changes in the museum until the Sackler Center opened. And it changed immediately, absolutely immediately. Suddenly curators were looking in storage. What had they neglected, or overlooked, or put aside? Within a year of signing the agreement the museum exhibitions started to change.

It took four years for the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art to be built; we opened in 2007. The space had housed the Brooklyn Museum costume collection and the Schenck House. So it had to be emptied. The costume collection was gifted to the Metropolitan Museum. Which is how I knew The Brooklyn was really serious about a center for feminist art!

VS: It’s amazing that while we see you breaking down walls and shifting conversations and building connectivity on the public platform you were also doing that inside the museum.

ES: And as we were doing that the museum changed and the curators changed. It was interesting because the curators were not jealous of all the focus on the Sackler Center, to the contrary, they were extremely excited because it was new energy and it was bringing life to departments that had sort of been drifting along.

VS: Sounds like you were fascinated by what other departments could offer to Herstory and they knew you wanted to tap into them and they loved that.

ES: And they were very very excited by what we were doing.

VS: Just out of curiosity, when you joined forces with the Brooklyn Museum were most of the in place curators male or did you inherit a lot of strong women curators?

ES: There were men and women curators. Amy G. Poster, for example, was the head of Asian Art at the time a very strong curator. I don’t know what the exact gender balance of curators was.

When Arnold invited me to join the board in 2000 there were about twenty five men and about four or five women on the board at that time. Now we’re thirty eight and the majority are women, two thirds are women. The museums entire senior administration is women with the exception of David Berliner who just came on as COO. The board officers are now all women. When I came on the board officers were all men.

VS: I noticed currently at the Brooklyn Museum, perhaps for the first time in the history of any museum, the three main shows, all major current exhibitions, are all women artists. It’s so powerful.

ES: Yes, It’s a great moment. It’s a really incredible moment. We’ve always had two women shows going on in the Sackler Center but with ‘Marilyn Minter: Pretty Dirty’ and ‘Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern’ accompanying our ’We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85’ it’s a full sweep throughout the museum. We’ve taken over the whole museum. That was the idea, to take over the museum. So far so good.

VS: While you were making all this happen has there ever been a moment when your jaw dropped because you were actually watching feminist progress being made right in the room where you were sitting?

ES: I think what dropped the jaw for me was how rapidly the Sackler Center had external influence. It was within months of opening. I hadn’t expected that we would have such an impact internationally, for galleries, for women artists, for feminist artists all of a sudden. There’s still not parity, as we know, but the improvement has been significant. Of course I watched as immediately the Whitney started looking and the Guggenheim started looking and the Met started looking. You can see that it’s changed. It’s changed, but we still have more to go. It wasn’t so much jaw dropping but it surprised me how quickly it happened. I thought it might take a year or two. I didn’t think it would take a month or two. Well it just goes to show you how hungry everybody is for women’s work. It really has less to do with the fact that maybe I had an impact by coming up with something. More it shows that there is an audience who is really hungry for this work. It taps into that. People really want it.

VS: We know how important it is for global solution seeking to get women’s voices into every arena right now.

ES: Well that’s true we have a long way to go.

VS: You work on that every week, every month every time you do a program.

ES: That was very important to me. That is why we created the Forum in the space too. We have The Dinner Party Gallery, the Herstory Gallery, The Feminist Gallery and the Forum. I wanted a space that would seat about forty or fifty people. The Brooklyn Museum auditorium seats four hundred. I knew that we would have a lot of programming, that was going to be very important, and if you have a hundred people in an auditorium that seats four hundred it looks like nobody is there. So we have our Forum. The museum at the time didn’t understand the importance of programming to the Sackler Center. The Sackler Center programming to me was always integral. Because the museum didn’t understand the import it actually gave me leeway the first year I was out there every Saturday and Sunday doing programming and inviting people to speak. I was basically curating the programming and all of a sudden the museum looked up and realized, wow, Gloria Steinem was in the auditorium and it was sold out, and talking about sex trafficking, and we’ve got something going here. The programming now is integral to the museum. Rebekah Tafel and I continue to do the social action portion. Our ‘States of Denial: the Illegal Incarceration of Women, Children and People of Color ‘ started almost four years ago, before mass incarceration and state sanctioned violence was headline news.

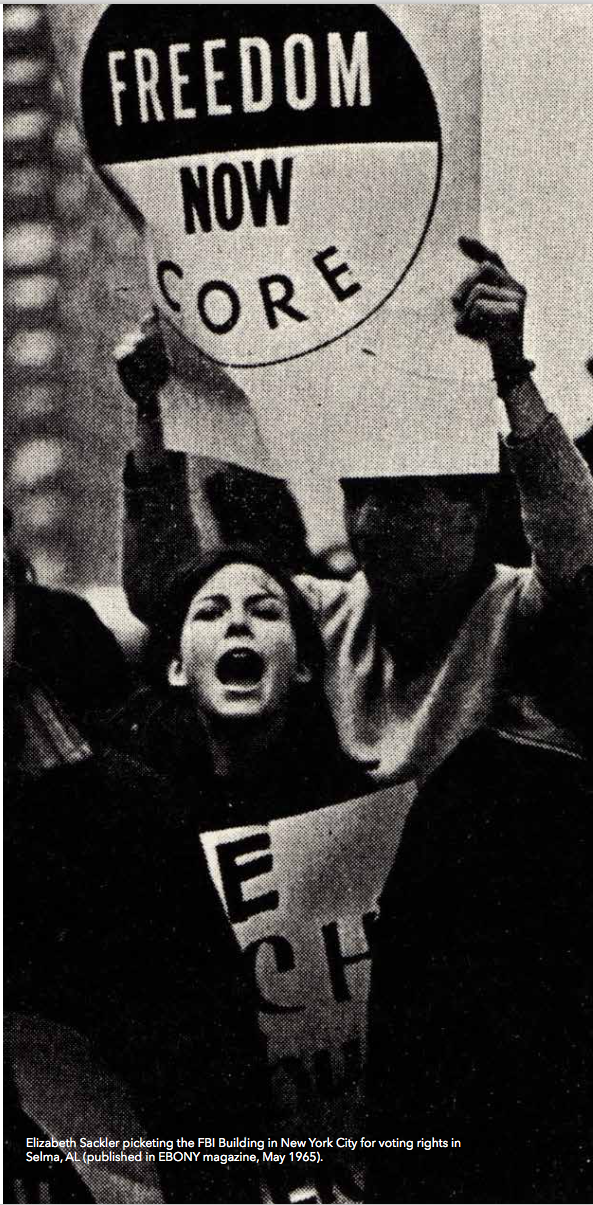

VS: I see a great photo on your desk of you picketing…it looks like you have always been an activist.

ES: Oh my gosh, that’s when I was 15. We were picketing the FBI building for voting rights in Selma Alabama. I grew up as an activist. I went to The New Lincoln School up in Harlem on 110th street my whole life. It was all about civil rights and social action. My parents were about equity and equality, moral and ethical action. I was brought up to do this. And because my father and my family had so much to do with museums I was able to watch my father negotiate and deal with museums so that I was prepared to negotiate with the Brooklyn Museum. I watched my father do it for decades.

VS: While watching him your brain must have been firing on how to bring the two together. Bringing social action to museums.

ES: I knew how to do it. I watched him do it. It’s like anything else, you have to be trained to do something so that it really works and I was well trained. I’m not a philanthropist. I consider myself a human rights activist with means.

VS: So you are a ‘firsty’ yourself.

ES: Yes, I guess I am. Definitely.

VS: How do you respond when women question if feminism is outdated?

ES: Nobody has ever said to me that feminism is outdated. The world that I live in is a world of feminists and feminist artists. But it was very interesting, on January 12, 2017, there was a panel discussion at the Museum of Modern Art just before Trumps inauguration. Catherine Morris, our wonderful curator whom I adore and I love working with her and we’re very close, was speaking. She had said before the election she had started to wonder whether or not we needed a center for feminist art. Then she said ‘but clearly we do.’ And everybody burst out laughing. I raised my hand after a little bit and I said that’s why I created the Sackler Center to exist ‘until we live in a world of equity and equality and justice’. I never doubted the need for it.

I think there were generations of women and young women who felt that we had reached post feminism. Catherine, even was wondering about it. And that sort of surprised me, but that’s cool, that’s fine. What I have adored about Catherine is what she has brought to the Sackler Center. When she came she asked ‘What do you want me to do?’ ‘what’s my mission?’. And I said, ‘We’re ahead of the curve, we’re writing the canon, we are breaking new ground and I want you to make sure that we stay ahead of it.’ MOMA and the Whitney and the Met and the Guggenheim all have money and we did not. But we have something they do not have and that is a commitment to community, a commitment to diversity, a commitment to taking risks. They have different commitments. Catherine keeps us ahead of the curve. How she has, and with the grace and intelligence that she has, is by opening the dialogue to not just feminist art as a category but what is the content of feminist art, what is feminism and what is feminist in art that we don’t see because we’ve been trained to see through patriarchal eyes. Even going back to classical times, in Egypt and in Greece, there is the power of women and we don’t see that. We’re not taught that in art history. It doesn’t take that point of view. So Catherine has really broadened the conversation about feminist content, and what it means to have feminist content. Our current exhibition, ‘ We Wanted a Revolution; Black Radical Women 1965-85’, is absolutely outstanding. We have completely busted open art history with this exhibition. To have black women artists, who in the 60’s and 70’s were already moving along in new directions, breaking ground, who often not even to this day, were not included in art history. It’s like Hanson not having any women in their art history until the 1980’s. Black women artists have been continuing to suffer from the same lack of inclusion and in fact omission and erasure. So what we are doing is exciting.

VS: These certainly are interesting times. With the social and political upheaval people are really starting to open their eyes. It has increased empathy and people want to reach out. But at the same time there are all these other walls being built perhaps between half of the women in America. How do we include them, bring them into the conversation?

ES: I haven’t the foggiest idea. This goes back to the Reagan era. Civics was not taught after the Reagan era in public school education. As a result we have a citizenry, no matter what color, no matter what economic background who went to school and did not ever learn how the government works, what the different parts of government are, how checks and balances work and what our civic responsibility is. As Obama said in his closing statement the Constitution is just a piece of paper. What brings it to life is the population, is involvement of people. What happened was a. we aren’t learning that it was a requirement and b. didn’t understand how our government functions as a democracy. That it all is grassroots. That it all starts with the congressman or with your school board person. That it all gets built from the ground up not from the top down. This has been a huge wake up call. I was reading on Twitter what somebody wrote if Trump has done anything he’s woken up the entire population. This may be his only contribution of his presidency, but it’s big. It’s great to see people opening their eyes and becoming active.

When I opened the Sackler Center to the women who were having trouble with the word feminism, I would say, if you believe you have parity now, you are not only going to hit a glass ceiling, you’re going to hit a cement ceiling and you’re going to end up with a migraine.

VS: And you might be sitting in a place where you are quite fortunate compared to others. If you can’t see the disparity for populations of women other than yourself then you somehow have blinders on.

ES: Yes, It’s been very interesting. I think the question of ‘intersectionality’, which is a term women of color are using, and ‘privilege’ which is popping up, is really beginning a new conversation.

It’s been very interesting to me. I graduated from high school in ‘66. I grew up in Harlem in a highly integrated school, the most integrated school in the city. There was no sexism. There was no racism. I encountered none of that till I went off to college. It was very very surprising. At that time I was sleeping in front of the White House for voting rights in Selma Alabama. It’s what we did. It’s what you did. When I read Ta-Nehisi Coates’s, ‘Between the World and Me’ it woke me up in a new way. His writing is so incredible I think for the first time I had an inkling of what it was to be walking in those shoes. More and more, I don’t know if it has to do with age. I’m not quite sure what it has to do with. My parents were young adults of the Depression. I’m a first generation American. My grandparents owned a grocery store in Brooklyn. My father was a genius and my mother never let us forget that whatever he earned was his, and how fortunate we were to experience the things that we experienced, traveling, art and so forth.

My father used to say to do x, y or z was a privilege. I would hear him say it in a speech for example when the Sackler Wing opened at the Metropolitan Museum. People now use the word honor, ‘it’s an honor to introduce so and so’ or ‘it’s an honor to be here today’. My father would talk about privilege, not as having privilege or being privileged. He didn’t use the word that way. But rather that it is a privilege to be able to… And it was very clear that we had to recognize that. I would say it has been a privilege for me to open a Sackler Center. It was a blessing for me to start the Repatriation Foundation. We’re coming up at a time of so much just discourse. I understand a lot about it because of the way I grew up.

I walked into ‘We Wanted a Revolution’ in the Sackler Center and I just had to stop and take it in because for me having that exhibition at the Sackler Center is what the Sackler Center is all about. It is totally what it is all about. It is bringing the voices and bringing the people and bringing the art to the people that have heretofore been ignored.

VS: I hear in your voice, that although you have spent your whole life as an activist, this moment is bringing up an enormous amount. What we’re experiencing as a country is urging women to excavate their pasts and try to make sense of where we are.

ES: Well I’m horrified with this country. I feel like we’re looking at a Nazi regime. I recognize things. I see a dismantling of our democracy. It is a horrifying time and yet so many are sustaining the protests, sustaining the resistance and learning what it is that they have to do to hang on to their rights as Americans.

I was actually at Gracie Mansion at the opening of ‘New York 1942’ and was speaking after the First Lady. I talked about ICE and I said I recognize that we are a sanctuary city and that the NYPD will not assist ICE with deportations of immigrants. But I said to the assembled crowd, ‘NYPD will not assist ICE but they will also not deter them. And if the NYPD will not deter them, then we have to’. We have to put our bodies in between ICE and those people who are being rounded up.

VS: How do you address these issues at the Sackler Center?

ES: I started ‘States of Denial; The Illegal Incarceration of Women, Children and People of Color’ in March 2014 and somebody had asked me why I was doing it at a museum.

Then a couple weeks later on March 20, 2014 Holland Cotter’s article; ‘Door to Art of the World, Barely Ajar’ in The Times’ Museums section talks about inequity and injustice in the museum world. He writes,’ Even unbuilt, the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi feels like a white elephant, corralled on the Island of Happiness with others of its kind: an Abu Dhabi branch of the Louvre designed by Jean Nouvel, and a performing arts center designed by Zaha Hadid, all constructed by people who will most likely never get in the doors and whose art is still hard to find in comparable museums in New York. Yet it would take a real cynic not to speculate about how this might be different. What if seemingly incompatible institutional features — humane local wisdom and custodianship of treasures of art — could be made to coexist? We’d have museums that are on the right side of history, and in which the future of art would be secure. That ideal is worth storming an empire for.’

And that is exactly what the Sackler Center does. It works with the community, it takes our art and our art history and it puts the two together so that we can see the past, so that we can see the future. And so I was thrilled with this article because then next time the question came up I was able to answer the question adding not only because I think it’s relevant but so does Holland Cotter. And as Arnold Lehman did so does our new director, Ann Pasternak. We are working on ideas about how to do that. For me ‘We Wanted a Revolution’ is an ideal example.

VS: I know that it’s very difficult to be everywhere and see what’s going on right now. But I can’t help but think that knowing what I’m going through, and what you are speaking of, and when so many women are soul searching and looking at everything that they’ve experienced in their lives that brought us here, and so many feminist artists are digging down deeper maybe than they ever have before, there’s got to be amazing work being made right now. Are you sensing or hearing about feminist artists doing new bodies of work?

ES: I don’t function in that world that way. I don’t go to art fairs. I don’t go on many studio visits. I know a lot of very well-known women artists. They are also of my generation, many of them are older.

VS: Do they call you and say, Elizabeth you have to see what I’m doing I’m so upset or I’m so moved or I’m so engaged in this.

ES: People don’t call me to come and see. I’m not a collector. My father was a great collector. My father was a real collector. It’s true I have a great collection of Judy Chicago works that I put together as a curated collection but I don’t consider myself a collector. So I don’t get those kinds of phone calls. I find that artists are like writers. You get pregnant with an idea and it needs to gestate. I’m writing in my head long before I ever sit down to a pen or computer. It needs to form. It needs to take shape. So I don’t find that women artists talk about how what they are working on right now is a result of the other. At least not the photographers and artists I know.

VS: I suppose I’m still a bit of an optimist. I think women artists across the country, with all they’re going through right now, must be making great art. Maybe it won’t surface right away. Hopefully it won’t take twenty years to shake it out.

ES: You will see it and I probably will not, just by virtue of our chronological ages.

VS: Do you have any other projects that you’re pursuing from an activist standpoint that you want to highlight? I loved the fact that you went into prisons to engage incarcerated women in artmaking and then brought the work into the museum.

ES: Yes, ‘Women of York: Shared Dining’ was incredible. Mass incarceration is an enormous human rights violation. Obama was starting to roll it back and whether or not that’s going to happen I don’t know with privatized prisons and the new administration.

VS: I learned a lot by watching the Sackler Center panel discussion. The stories about the young girls in foster care getting incarcerated for not making their beds. This is information that needs to be heard.

ES: We have a huge huge human rights problem in this country. We always have. Whether it’s been against the First Peoples, Native Americans, whether it’s been against African-Americans. The good news is it’s all bubbling up to the top. The great news is that people are seeing it. People who either weren’t paying attention, didn’t see it, didn’t know, were too busy doing whatever, buying shoes, are now seeing it. And that’s a great thing and it’s the only way we are going to make progress. Progress right now is going to have to be rolling back a whole bunch of things in order to move forward.

Last night I was listening to the first half hour of Obama at the University of Chicago. He was there talking to students. The fact of the matter is that for twenty minutes he spoke clearly, eloquently and with a point. I thought, my God, have we actually forgotten what it is to have a President who is speaking in full sentences, in full paragraphs, with a clear point, actually speaking English that you can understand?

VS: And with some deep thinking behind it. Some heart and soul behind it.

ES: Just sentences, forget the heart and soul, we’re talking about being able to put together sentences and have information and a vision. But in any event I don’t want to end there.

I think there’s a lot of work to be done and I think it’s great that there are new generations of people doing it.

VS: Thank you for being a ringleader and an instigator, for making sparks fly and things happen.

ES: It’s been a pleasure and it’s been a privilege.

Photo credit: Jurgen Frank

Opening Dinner for We Wanted A Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85 at the Brooklyn Museum (April 20, 2017). Photo credit: Elena Olivo

Arnold Lehman and Elizabeth Sackler at the 2015 American Federation of Arts Gala

Elizabeth Sackler and Judy Chicago at the opening of Judy Chicago: A Survey at the National Museum of Women in the Arts (Washington, D.C., 2002)

Photo Credit © 2012 Philip Greenberg.

IN THIS IMAGE

Elizabeth A. Sackler and Yoko Ono

November 15 2012

Brooklyn Museum Yoko Ono

Tenth Annual Women in the Arts Benefit Luncheon

Introduction by Museum Director Arnold L. Lehman followed by a conversation between Ono and Catherine Morris, Curator of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art.

Multi-media Conceptual artist Yoko Ono was be honored at the tenth annual Women in the Arts luncheon Thursday, November 15, 2012. Proceeds from the event benefited the many educational and artistic programs offered by the Brooklyn Museum and its Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art.

The program began at 11 a.m. with an introduction by Museum Director Arnold L. Lehman followed by a conversation between Ono and Catherine Morris, Curator of the Sackler Center. The program concludes with the presentation of the 2012 Women in the Arts Award to Ono and a reception and luncheon in the Museum's Beaux-Arts Court.

Interviewer Victoria Selbach is a feminist painter focusing on women. Selbach's recent work, Generational Tapestries, excavates feminine identity as it is passed from our foremothers to our daughters.